Subscribe

Links

Sponsor: Essential Endurance Rider Fitness – The only personal fitness program designed specifically for endurance riders, by an endurance rider

Show Notes

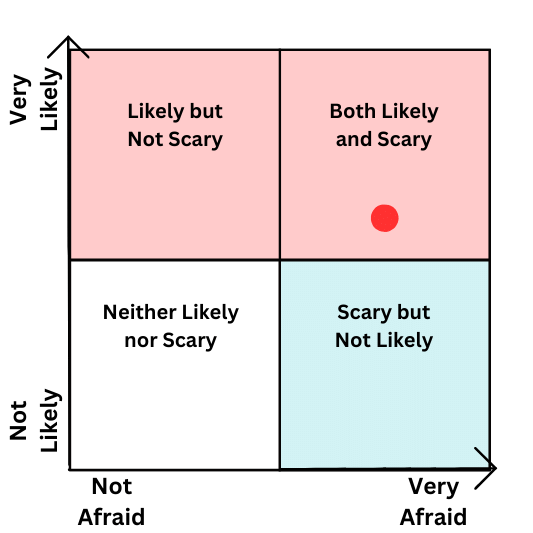

Use this model to help determine whether you most need a practical or psychological solution to your fear of conditioning your endurance horse alone.

In the example below, the placement of the red dot indicates that the specific fear is both very likely and very scary.

If your fear falls into one of the upper two, pink quadrants, it is probably best addressed with a practical solution. If it falls into the lower quadrants, it is probably best addressed with a psychological solution.

Transcript

Hey rider Tamara here from the Sweaty Equestrian, where we explore optimal performance for distance riders. Today’s topic is by listener request. We’re going to talk about how to overcome your fear of conditioning your endurance horse alone. I think this is a really common fear and it’s also a big problem if you want to be a serious and effective endurance rider. It’s obviously much more difficult to ensure that your horse is ready for your goal ride when you have to rely on others to be there for every single conditioning ride. And also, even if you do get your horse conditioned by just riding with other people, what happens if your buddy pulls during the ride? Then what? How disappointing would it be to have to pull from that ride you’ve really been looking forward to, just because you feel like you can’t go on alone? So let’s talk about this how can you overcome your fear of conditioning your endurance horse alone? The solution is not necessarily easy, but it’s usually possible. But we have to start by identifying what the correct solution is based on, what the actual problem is.

Now, I have dealt with fear in the past myself. Years ago, I had a bad fall when my horse spooked at a rattlesnake, spun around, started bucking downhill. Long story short, I came off and actually cracked several vertebrae in my low back and of course, getting back on involved a certain amount of challenge and getting over fear. So I thought back on that experience as I considered this question and I found myself putting possible solutions into two different buckets practical strategies and psychological strategies. So step one in dealing with fear of riding alone is to identify which of these practical or psychological should be your focus.

Now how do we go about figuring that out? Well, we have to consider why we’re afraid. What are we afraid of about riding alone? If you’re like most of us, your experience of fear likely shows up as generalized dread, you know. Maybe you feel it between your shoulders or in the pit of your stomach. Maybe you procrastinate or make excuses not to ride. But have you ever considered exactly what it is that causes that generalized feeling of dread or anxiety? What exactly is it that scares you? This could be a lot of different things. Maybe you’re afraid of losing your horse miles away from the trailer. Maybe you’re afraid of getting injured out there alone because you fall. Maybe it’s about being able to control your horse when he doesn’t have the company of other horses. Maybe you’re concerned about encountering dangerous people or animals.

Close your eyes for a second unless you’re driving and imagine the entire process of going for a solo ride. Just think it all the way through, from catching your horse to the trailering, the ride itself, the haulback, the unsaddling, everything. What part of the scenario provokes your anxiety? Try to put your finger on where your lack of confidence is coming from. Is it your personal riding ability, a past incident, a horse behavior issue or something else? You might even realize that your fear isn’t about riding at all, but actually about towing the horse trailer. So think this through for a second. Go ahead, jot it down. Once you’ve identified exactly what you’re afraid of, jot it down.

And now let’s move on to determining whether that fear, that specific fear, is proportional to the actual risk of that thing happening. To help us visualize this, imagine a square that’s divided into four quadrants. Along the bottom of that square we have our horizontal axis, and that’s where we’re going to rate how afraid we are of this specific thing that we’ve identified. On the left we say I’m not all that afraid, and over on the right hand of that axis, that’s where we’re very afraid. Okay, so think about the thing you’re afraid of, and are you very afraid of it or not very afraid of it? Okay, and then on the vertical axis we’re charting how likely that fear is to actually come true in real life. So the bottom is it’s not actually that likely and the top of that axis is it’s very likely.

Now what we can do is use those two axes to plot where our fear falls in those four quadrants. So imagine that what you’re afraid of is very likely to happen, like it’s a genuine fear, and also you’re very afraid of it. Your dot would go up in that upper right quadrant. Suppose it’s something that is very likely to happen but you’re not actually all that afraid of it, then it would go in the upper left quadrant. If it’s something that you’re not terribly afraid of and it’s also not terribly likely. If it’s something that you’re not terribly afraid of and it’s also not terribly likely, that would go in the bottom left quadrant. And if it’s something that you’re very afraid of but it’s really not very likely, that’s going to go in the bottom right quadrant. Now, if you’re having trouble picturing this, I will put the chart in the show notes so you can see how this works. Now, of course, because we all live only inside our own heads and with our own fears. We may not have a super clear read on how likely the fear is to actually come true, so it might help to enlist the help of a friend who knows you and the horse in question to help you determine whether or not that fear is super realistic.

Okay, so think this through. For just a second, place a dot on your mental chart where your fear level and the likelihood of it happening intersect. Picture what quadrant that falls into. Is it likely but not that scary? Is it both likely and scary? Is it neither likely nor scary? Or is it scary but not likely? Got it Okay.

So next we’re going to determine whether dealing with this particular fear requires a practical focus or a psychological focus. So if the thing you’re scared of fell into a very likely quadrant, so one of the top quadrants either likely but not scary, or both likely and scary the thing that you’re afraid of probably has a practical solution. So, regardless of your actual level of fear, that scary thing really could happen. The good news is that you can break down that danger into fixable pieces, and we’ll get to that shortly. If you landed in the bottom half of the quadrant where it’s neither likely nor scary, or it’s scary but not likely. That means you need to probably take more of a psychological approach Now. That certainly doesn’t mean that your fear isn’t real. It just means that the thing you’re scared of isn’t likely to actually happen. But your mind and body still need convincing Now, if you’re in that bottom corner the bottom left corner of neither likely nor scary, chances are that you are already managing a mild fear of something that’s unlikely by taking reasonable safety measures and keeping your imagination under control.

So well done. Now the nature of fear falls along a spectrum right. There’s a good chance that all of us will benefit from both practical and psychological steps to overcome our fear of riding alone. And also one more note on the upper left quadrant likely but not scary. If you happen to fall into that box, I would encourage you to deal with the issue anyway, even though you’re not terribly afraid of it, because it will make your horse safer for other people. If this is an issue that could be dangerous or frightening to somebody else in the future, it’s usually a good idea to deal with it, regardless of your own fear level.

For those of you who landed in the upper quadrants likely but not scary, or both likely and scary. Let’s talk about practical solutions, practical steps. You can’t meditate your way out of rational fears, right? Nor should you. Rational fears need to be addressed by changing the facts. So look at that specific fear that you’ve written down. What fact would have to change for that fear to diminish? For example, I’d have to be confident backing my horse trailer, or I would know how to change a tire, or my horse wouldn’t jig on the trail, or my horse would cross water, or he would stand still for mounting, or he’d be less spooky still for mounting, or he’d be less spooky. Or maybe I’d be confident that I could stick a spin or mount from the ground, or that I would know how to help if my horse got injured. The good news is that in most cases, these facts, whatever they are, can be changed by training your horse yourself or both. The bad news is that it will take time and effort and possibly a significant amount of time and effort. So let’s start with the horse. If your fear stems from your horse’s behavior or anticipated behavior, what do you do? Or anticipated behavior, what do you do? Some horses are prone to whirling and bolting when they’re spooked. Others refuse to go forward. They might buck or rear as part of that refusal. Some have annoying habits like not standing still for mounting or refusing to cross water. That don’t really matter at home, but they become a real problem when you’re out alone on the trail, whether it’s conditioning or at an actual endurance ride and like thistles in your pasture. These training gaps are easily ignored when they’re young, but they can grow into impenetrable barriers. If you want to trail ride alone and condition an endurance ride with confidence, it’s time to get rid of those thistles. Depending on your fear level and training ability, you might want to enlist a good trainer to help you get your horse to a point where you feel comfortable proceeding on your own, or maybe you just need to commit to putting in the training time on your own.

Personally, I find that I can work through most behavioral problems by breaking them down into steps that the horse and I are comfortable with. Sometimes I say if it isn’t easy, it isn’t time, and what I mean by that is if something doesn’t feel like a next step that we can handle, if it doesn’t look pretty easy, then I need to back up and take an even smaller fraction of that step and work my way up with the horse more slowly. If I feel the fear rise in me, I need to scale back to a manageable prerequisite that will move us in the right direction. I also find that when the environment changes you know, moving from the round corral to the arena or the arena to the trailhead I may need to go back and repeat earlier training steps. Sometimes this means hauling out to the trailhead and just training near the trailer and then going home instead of actually conditioning. Yes, it’s boring, but you have to do it sometimes and it’s worth it to have a solid horse that you can fully enjoy for years to come.

Another thing to think about is putting more tools in your toolbox, giving you more options of what to do if things start to go sideways. For example, I never ride a horse out of the arena until it has a few skills down 1000%, and these are tools that I can pull out in a heartbeat if something starts to go sideways. For me, this includes a rock-solid single rein stop, including the hindquarter disengagement. I want a responsive bend on a tight circle and I want lots of groundwork options things I can have my horse do on the ground to get him to concentrate during touchy moments on the trail, so this might be sending him back and forth or in circles around me backing up walking figure eights, things like that. I teach these skills in the round corral and the arena until both the horse and I can do them on autopilot, and then when I head out to the trail I keep right on drilling them until I am confident that they’ll carry over even in a tense situation. I want it to be super automatic. Finally, even though it’s not my favorite task, I do practice riding my horses in undesirable conditions like wind. I really hate wind and slick footing and I do this at home so that it’s not novel when we encounter those conditions on the trail. That takes a lot of the anxiety out of those situations down the road. So you have to do the work when and where it’s needed.

You know some issues are hard to work on at home because they simply don’t happen there and, as frustrating as it is, you might have to sacrifice a lot of trail rides and maybe even paid endurance rides to focus on training. I’ve had horses who were really pretty reliable until we got to an endurance ride, and then he would absolutely lose his mind and I would have to spend a whole lot of the first loop with no objective beyond dealing with his mental state, dealing with that issue at hand dealing with that issue at hand. So to manage your fear while training in a real deal situation, you might have to do a lot of groundwork. A horse that’s fine at home, but anxious alone on the trail, is going to benefit from a lot of hand walking, for example, and to that point there’s no shame in getting off, either during conditioning or at a ride. Handwalking gives you a safe opportunity to see how your horse is going to react to everything, from quail fly-ups to cars. He can work through his nerves while you build your relationship, and you know some extra fitness to boot.

Now what if it is your own skill that needs improvement? That’s actually great news, because whether the ability you need to ride alone with confidence is more of a mental thing or a physical thing, you can acquire that, so you might have to learn new skills. Are you, for example, afraid to ride alone because you feel like you’re unprepared to deal with a potential problem like an injured horse or a tight parking space? You can study equine first aid or recruit someone to teach you how to maneuver your trailer. I actually made friends with a local commercial driver’s license instructor who gave me a lesson in trailer backing, and I tell you what that was a game changer for me.

Maybe you’re worried about wild animals and you need to educate yourself about the critters in your area and their natural behavior. Maybe you’re not fully confident in your riding ability and this is a good time to invest in some lessons. Work on improving your seat. Pick up some skills for dealing with dicey behavior. If it feels better to you, maybe see if you can borrow a mellower horse when you first start taking those new skills out on the trail. Also, an instructor can help you determine whether the horse you have is the right one for you at this point in your journey. I will say that is not always going to be the answer you want. The lowest point in my own journey through fear was selling a really gorgeous, well-bred mare who had a rearing problem that I didn’t feel equipped to solve. This was my first training project after that wreck when I broke my back. If I had that same horse now I think I’d be more willing to work her through it, but we were not a good fit at that time and that’s okay.

Another thing that you can do is improve your own physical fitness. If you’re afraid of being able to walk out, if your horse dumps you miles from the trailer, or if you struggle to mount from the ground or you’re not confident that you could do an emergency dismount if your horse bolted, these physical limitations can put a real damper on your confidence when it comes to trail riding alone. But again, good news, these can almost always be improved on. So if you’re hampered by pain or limited mobility, you might be surprised by how much the right medical care, physical therapy or just plain old increased fitness and mobility work can help. I would encourage you to look for help with those physical limitations. Yes, it will take time. Physical changes don’t occur instantly and usually it’ll cost some money, but it could change your life.

In an excellent post that she wrote, Jen Aristotle Balleau wrote that rider fitness does not mean a marathoner’s level of cardiovascular fitness or being the skinniest person in the room. For most equestrian disciplines, the cardio demands are low to moderate. Motor control and strength, however, are non-negotiable If you are going to help your horse use the orchestra of all his muscle groups. Well, you need to maintain your own, and I 1000% agree with that assessment. A horse that’s well-ridden by a fit rider is less likely to stumble on the trail, possibly hurting himself or you. And if you do find yourself injured and alone, being strong could help you self-rescue.

There’s a famous saying from the old-time strength trainer, Mark Ripito. He used to say strong people are harder to kill than weak people and more useful in general. True story For ambitious trail riders. There’s an argument to be made for sufficient cardiovascular fitness to walk over hill and dale to the trailhead if your horse heads that way without you and I have had this happen. If this is an area you want to work on, check out my Endurance Rider Fitness program, because it will cover all these things Mobility, strength, cardiovascular fitness, all targeted specifically for endurance riders. It’s called Essential Endurance Rider Fitness and you can learn about it at TheSweatyEquestrian.com/fitness. Solid training for your horse, your brain and your body may be all that you need to hit the trail with more confidence. However, most of us who have an issue with fear need to prepare ourselves psychologically as well, so let’s talk about that.

Next, we’re going to explore how to leverage the mind-body connection to manage riding-related fear, even when it’s disproportionate to actual risk. The mind-body connection sounds a little woo-woo, but science actually assures us that it’s real. From our guts to our hip flexors, our bodies are inextricably connected to our brains. This, again, is good news, because it means that we can learn to manage our fear response, even that physical fear response, by using our bodies and brains to calm each other. Here are some thoughts on how to do that. First of all, you need to curate your thoughts. See, our brains are perfectly capable of reacting to imagination as though it were reality. Obviously, this is a very bad thing if we are dwelling on our fears. There’s nothing more sickening than lying awake in your horse trailer the night before a ride, picturing yourself tumbling over a cliff with your beloved horse right. So why not leverage your imagination to your advantage instead of your disadvantage? To your advantage instead of your disadvantage?

Athletes have long used visualization to calm performance anxiety and hone their skills, even when they’re sidelined with an injury. A paper from the International Coach Academy puts it like this quote if you exercise an idea over and over, your brain will begin to respond as though the idea was a real object in the world, and thus any idea, if contemplated long enough, will take on a semblance of reality. Your belief becomes neurologically real and your brain will respond accordingly. Unquote. So try holding an if-this-then-that planning situation with yourself. Imagine the thing that you fear happening, and then here’s the key visualize yourself handling it safely and effectively. Running this positive visualization repeatedly through your head will not only ease your anxiety in the moment, but it’ll prime you to respond effectively if that scary event does actually occur Now, help from a therapist may be needed to go beyond what you’re able to accomplish on your own. I have not tried this personally, but many writers report that something called the emotional freedom technique, or EFT, or eye movement, desensitization and reprocessing, emdr, can relieve anxiety, particularly from traumatic memories. I can speak personally to the benefit of EMDR, but in my case the issue was not horse-related, so that might be something to check out with a mental health professional. Another thing you can do to get over fear of riding alone from a psychological perspective is to leverage mindfulness.

Now, mindfulness is a term that gets thrown around a lot these days, not without reason. At its core, mindfulness is simply limiting one’s attention to the reality of this moment, observing your sensory experience and your reactions without judging them, and the last few decades have churned out reams of research on the benefits of mindfulness. It can be particularly helpful when our fears are the result of prior bad experiences, like that fall when I broke my back. There’s a study by Sarah Lazar indicating that we can decrease our experience of fear by changing our focus from the bad memory to the present reality. She says mindfulness can enhance our ability to remember this new, less fearful reaction and break the anxiety habit. So the idea here is to consistently interrupt those old, fear-inducing memories, eventually replacing them with new and less threatening associations in the mind. Lazar suggests that when we begin to feel anxious, we actively respond by redirecting our thoughts to the present, and then we should encourage curiosity about our inner and outer experiences as they play out. So we’re focusing on what’s actually happening rather than the bad memory that is causing the anxiety in that moment.

Another thing we can do is use our breath. Now, focusing on the breath is an ancient tenet of mindfulness. I’m sure you’ve heard of it Diaphragmatic breathing, which is generally practiced as inhaling deeply through the nose and letting your lower belly expand. You can practice that any time, including in the saddle, and you might even find that it quiets your horse in addition to your own nerves. I know that I used that during the first 20 miles of Tevis and it actually did seem to help. Many riders find that singing is a more natural way to encourage deep breathing while you’re trotting down the trail, and nobody needs to know whether you can carry a tune because, remember, you’re riding alone. That’s the whole point. Just pick a song that makes you happy and serenade your horse. Breathwork actually has a direct physical effect on our autonomic nervous system and it ultimately exchanges hypervigilance in the brain for relaxed alertness. So it’s worth a try.

Months ago I stumbled across a social media post by Dandy Rudy of Rudy Horsemanship, and in her post Rudy explains how fear makes us involuntarily contract our psoas major, which is a muscle deep in our core that connects the spine to the femur, so it kind of runs through your pelvis. When we contract that psoas major, we go into the fetal position. So when fear makes us involuntarily contract the psoas major, what do we do in the saddle? We kind of crunch down and we don’t sit up straight. Right, you know that feeling Because our muscle groups work in opposition to each other. So think of your biceps contracting while your triceps extend and vice versa. Or your hamstrings contracting while your quadriceps extend.

The way to relax your psoas major, which is going to crunch your thighs towards your rib cage, is to tighten the gluteal muscles, because those are the ones that oppose your psoas major. So when you tighten your gluteal muscles, your butt muscles Rudy calls this engaging the confidence button. It’s kind of like pushing a button on your tailbone to tighten those gluteal muscles and release the psoas major so that it relaxes and you don’t go into kind of a miniature fetal position on your horse. Here’s how she describes it. She says pretend you have a button right at the top of your butt. Crack that. When you press it down into the saddle it will flood you with sticky super seat powers, because it does. When you tuck your tailbone, lift your pubic bone and engage your lower abs, it opens and relaxes your hip joints. And guess what that does? Oh, it enables you to sit most evasions or spooks that your horse may dish out.

There’s nothing like an afternoon alone in nature with your horse to bond your relationship and wipe away the stress of daily life. Also, it sets you free to do the conditioning that you need to do when you want to do it, so that you can go out and do the endurance rides that you want to do, and you can ride those alone as well, if that’s how the day goes. I’m reminded of a favorite poem of mine. It’s by Erin Hansen, and she wrote there is freedom waiting for you on the breezes of the sky, and you ask what if I fall? Oh, but my darling, what if you fly?

Look, there’s no doubt that fear can be powerful, but it doesn’t need to be overwhelming, it doesn’t need to keep you from conditioning your horse alone. So here’s what you’re going to do Identify the specific source of your fear, determine the appropriate practical or psychological solution, or maybe a mixture of both, and then take on that solution in manageable steps. Hey, the time is going to pass anyway. So what do you have to lose? Go, put in the work and optimize your endurance riding.