Foresthill

The road into Foresthill was lined with sunburned, cheering crews in matching shirts. They trundled carts full of tack and sponge buckets, craned their necks to identify incoming riders.

Astride Atlas’ confident walk, I scanned the crowd for familiar faces.

There!

One, two, three of my crew – all smiling and giving me instructions, taking over Atlas as they chivvied me ahead on foot to where Mr. Sweaty and Layne waited. Layne, with her walker and still non-weight-bearing leg, had hobbled all the way up there to catch us coming in.

Their immediate concern was for my lungs, which were still uncooperative, but manageable. Then for Atlas, who was being untacked and sponged as he walked, looking around himself with bright-eyed interest.

We went straight to the vet, where Atlas blew us away with fantastic scores. Everyone around watched with wide eyes. “He looks amazing!”

Then, he was swept away with my exceedingly-capable crew while Mr. Sweaty shuttled me to a friend’s rig. Oh, thank god. Finally, I could change clothes!

Sweating profusely in the hot trailer, I peeled off my sodden breeches. Slathered on new zinc oxide and hydrocortisone cream on my legs, where I tend to get heat rash. Dressed in a complete set of dry clothes, from socks on up. Laced my feet into dry boots, which felt like heaven on earth.

Then, Mr. Sweaty led me through the maze of trucks, trailers, and crews to our own pop-up tent. Layne sat in a camp chair, holding Atlas’ lead rope while he ate. I caught her up on our experience so far as I, too, tried to follow my own, pre-typed Note to Self: drink iced coffee, take Aleve and Pepto, eat carbs and protein, check headlamp, charge phone, make sure water and electrolyte bottles are refilled.

And then, the saddle was back on and rockstar crew member Siri was leading me toward the trail. We cracked the glowsticks on Atlas’ breastcollar while the final minute of our hold counted down.

Unbelievably, the first hints of dusk had begun to gather as Atlas and I slipped away from the noise and bustle, back into the silent wilderness.

The world seemed somehow bigger now, more hollow and lonesome and mysterious. We’d come so far, seen so much. Yet it still felt like a kind of beginning, this solitary trot into the night.

Darkness overtook us as we descended yet another set of switchbacks. Oh, I thought as Atlas marched along a trail I could no longer see, though the trees remained silhouetted against a navy sky. Oh, this is going to be challenging.

At the bottom of the switchbacks, a handful of riders caught and passed us. They trotted briskly up the invisible trail. Hmm. Well, okay. I let Atlas pick up the pace as well, though I was still holding him back and straining to see.

Navy melted into black. A little moonlight filtered through the trees, but mostly the trail was a ribbon of ink that only sometimes looked different from the slope and vegetation around it. And this was no wide, groomed trail!

We were still navigating singletrack with all the same ruts and rocks and overhanging branches as we’d traversed in daylight, except now I could only squint ahead in vain. This isn’t going to work, I told myself. It’s going to be a very long, stressful night if I keep this up.

There was nothing to do but stop trying. I had to trust Atlas. I relaxed my eyes, kept very light contact on the reins, and focused on letting my seat follow Atlas with no notice of what might be coming next. He veered around turns, lifted me up steps, sent small, unseen rocks crackling into the brush.

When we hit a steep climb, I followed another rider’s advice to make sure Atlas didn’t cut too close to the inside of the switchbacks, as there might be drop-offs there. Knowing we clung to the side of a precarious slope, though I couldn’t see it, I slowed him to walk.

He was marching along when we saw a scrum of moving lights and reflective vests ahead. A swarm of people seemed to be moving up and down a section of trail. They paused for us to pass, pressing themselves against the bank as we brushed by. Up close, I could see their vests and gear: Search and Rescue.

On a switchback, we passed a dismounted rider and her horse, looking concerned. But this was no time to pester anyone with questions. Our job was to keep moving and stay out of the way.

At last, we broke out at the top of that treacherous climb. What a relief to be on flat ground! It was only for a while, though, because soon enough we found ourselves on singletrack again, switchbacking down and down.

Somewhere in this stretch, on a black switchback with a jagged drop on our left, Atlas slammed to a halt. A tiny creek, terrifying in the dark, burbled across the trail. Atlas took a hasty step back. I urged him forward, but he wasn’t having it.

Stuck on this narrow trail, with a cliff below, was no place to battle it out. I dismounted, slipped on the wet rocks, clung to the stirrup to keep from falling. I tried sending Atlas over the creek ahead of me, but no dice.

Well, shoot. I made the unconventional decision to cross ahead of him, in full awareness of the risk that entailed. Sure enough, as soon as I was across, Atlas leaped after. He plowed into me with his shoulder, but at least I’d been expecting it. I kept my balance. Climbed back on. Rode.

Francisco's

At long last, the vet check at Francisco’s swam out of the darkness. It was a crowded, stressful place in a flat spot that felt too small for all the horses packing in, despite the absence of crew. There were muddy spots in the grass. Trampled hay. Horses everywhere to dodge, trying not to get kicked as we called for a pulse.

Atlas was down almost immediately. He vetted well, then ate and drank despite the chaos. Stress seemed to run high among many of my fellow riders. People and horses were tired. Competitive. Concerned.

After a brief rest, I was glad to put Atlas’ bridle on and ride back into the night. Fifteen miles to Auburn.

By now, I’d reached a comfort level with trotting in the dark. I had accepted the strangeness of moonlight and shadow. They turned trees to boulders and grass to silver streams. The trail itself was dark; follow that! Or rather, let Atlas follow it. He seemed to know where the turns were, though I couldn’t see them until his body had already curved.

American River Crossing

Up there, somewhere, lay the American River. I could feel, even smell, that we’d dropped to its level. Kept expecting it around every bend.

When we reached it, the riverbed was untidy. The route to it crossed some odd, rocky patches, like a delta, as we followed glowsticks to the bank. The greenish bars split into two lines, forming an eerie lane beneath the surface.

Ready, Atlas?

He plunged in. So deep, so fast!

Within a couple strides, the water was up to Atlas’ chest and filling my boots. I felt a pang of mourning for my dry socks. Then, the water got deeper. And deeper. And deeper. Steadily, step by step, until Atlas was holding his muzzle high and water swirled around my thighs.

Holy smokes, was this right? Could I possibly have misunderstood the glowstick lane? Surely not. This had to be the way!

Atlas faltered. I felt the current shove him broadside, imagined us separating and washing downstream. It was on me to make sure that didn’t happen!

I threw my heart to the faraway bank and urged Atlas to follow. “That way, buddy! You can do it!”

He lunged on, a little deeper, then shallower, then deep again as we neared the opposite shore. “Yes! There you go! Good, brave boy!”

Atlas hauled himself out of the river and shook. Sparks of water flew off us in the warm night. Cooled, but not chilled, we trotted on.

Lower Quarry

Here was a long stretch of two-track. Atlas and I traveled alone, though I occasionally detected other teams in the distance. As we trotted, I began to sense that his movement wasn’t quite right. He’d slowed a little, and his hindquarters felt uneven.

I stood in the stirrups. Concentrated. Yes, there it was again. His left hind didn’t seem to be pushing as hard as the right. Also, was he sore in front? After this many miles, that might have been general weariness, but the hind was definitely uneven.

Uh-oh.

I slowed him to a walk. Somewhere in Auburn, I knew Layne would be watching our GPS dot on her phone, concerned.

“She’s slowed down because it’s the best thing for Atlas,” Layne later told me was her explanation to the rest of the crew. She knows me well.

We walked the remaining miles to Lower Quarry. For the first time, Atlas’ score on gait and impulsion dropped from A to B. “He’s a little tight back here,” the vet confirmed. “And does he seem a little touchy on the right front?”

I agreed on both counts and told the vet I was thinking of walking all the way in. He nodded and studied his watch. “You can make it,” he said. “Be careful not to rest here too long.”

I wasn’t sure if he was concerned about cramping or going overtime, but I was keenly aware of both hazards. We had six miles to go and it was approaching 3:00 a.m. We had about two hours to finish. Doable. Definitely doable.

I dosed Atlas with all the electrolytes and BCAAs I had on board, let him eat for a few minutes, and then we were off again.

Plenty of horses passed us as we walked. Atlas moved steadily, happy to walk fast but still feeling uneven behind when we tested a moment’s trot.

To my surprise, I felt physically well. Slowing down had let my lungs relax. I was neither sleepy nor particularly sore. I had no vertigo or skin rubs or screaming muscles. I was content to speak quietly to Atlas, feel the exchange of our bodies’ heat through the saddle, the steady swing of hooves and reins.

That section of trail gave me time to accept that we likely wouldn’t complete. Of course we’d try. Of course I desperately wanted to. But as willing as Atlas was to march and eat and drink along that stretch, I knew he’d be off at the trot. In fact, for the first time since I’ve known him, he declined to trot when I asked.

Still, I thought. Still, how magical to be out here! “Look, Atlas! This is No Hands Bridge. Can you believe it?”

The Finish

Then we were scrambling up a steep, crumbly slope. I saw lights ahead. Heard voices. “Rider coming!”

Cheers. A banner. Congratulations!!! 100 Miles!

And then we were there. Mr. Sweaty and Siri met us. I stepped down. “We have our work cut out for us,” I told Siri. “He’s tight in the left hind.”

We walked together down the steep road from official finish to fairgrounds around 4:30 a.m. Plenty of time…but as I mounted one last time to ride Atlas around the track, I knew it likely didn’t matter. He was tired but bright-eyed, hungry, freshly tanked up on water…but he didn’t want to trot.

The emotional disconnect between finishing (massive accomplishment!), yet probably not completing (argh!), made our trip around the stadium surreal.

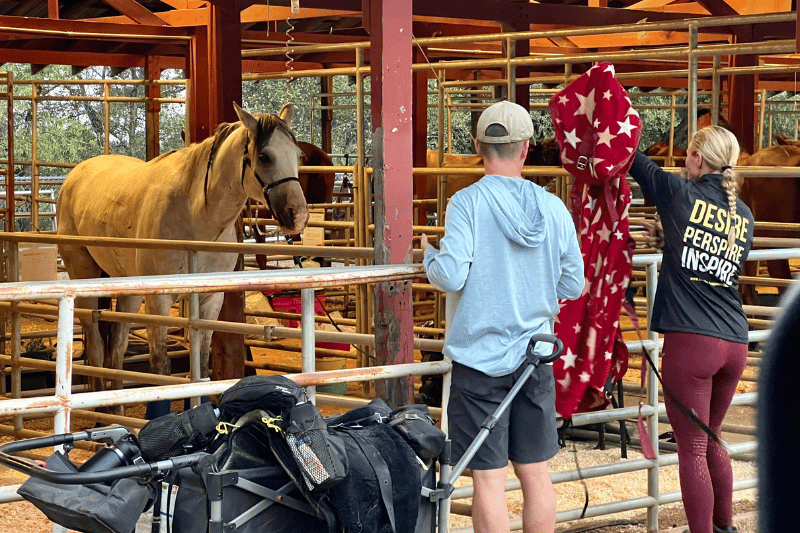

Just beyond the track, Layne waited with the rest of our crew. I could tell by her face that she knew we were on a knife’s edge. We all hustled to untack Atlas and massage his hindquarters as he dove into some hay.

And then, he lurched. It was a weird, rolling movement that seemed to start in his flank. Layne and I exchanged looks. “Did you see that?”

He did it again. And again. Now, our whole crew was trying to figure out what was going on.

The lurching movement grew until it seemed to ripple through Atlas’ whole body, from neck to tail. Then I spotted it: a dribble of green goo from his nostrils.

“Is he choking?” I asked in disbelief, at the same time as Layne said, “He’s choking!”

I ran to find a vet. She couldn’t work on Atlas herself while he was still hoping to complete, but she walked us through a delicate massage of his neck and the sponging of water down his throat. He coughed up some small wads of hay…but no real luck.

Decision time: Were we going to pull and send Atlas for treatment, or try to trot out and complete first? The helpful vet was comfortable with either choice.

Layne and I conferred briefly, even made a quick attempt to see if Atlas would trot. But no, he still didn’t want to, and we both agreed: Horse before completion. Always.

Off to the vet barn!

We got Atlas into a stall and opted for IV fluids as a first line of treatment. That alone might clear the choke – which already seemed to be improving – and any horse having just covered the entire Tevis trail would benefit from hasty hydration in any case.

We found Atlas a blanket. Sat with him. Watched him relax and brighten with remarkable speed.

Even though I knew he’d be all right, I wanted to stay with him. He’d carried me so far, and his health was my responsibility! But Layne insisted I go get some sleep, along with our drivers. It was shocking to think that we’d be headed partway home later that same day.

And so, reluctantly, I followed Mr. Sweaty to our trailer in the fairgrounds parking lot. I showered. Climbed into bed. Tried, and failed, to sleep.

A couple hours later, when the interior of the LQ had grown too warm for rest, I gave up and checked my phone. I had a text from Layne assuring me that she’d spoken with several vet friends who rallied to help. Atlas is CHOWING now, she wrote. Looks completely normal.

I also had a Facebook message from one of my favorite endurance vets in the world, who wasn’t on site but had heard the saga from Layne: You did everything right!!! You didn’t know fat kid was gonna dry month down dry food!!!! You both did phenomenal.

I laughed out loud, and maybe cried a little. It was exactly what I needed to hear.

I also heard from Layne what I already knew (but needed anyway):

There was no accusation, no upset, no blame. Not only was Atlas fine, but she was proud of us. It’s a rare thing in this world – a friendship rich with communication, mutual ambition, respect, confidence and trust. That, plus a bond with Atlas that could only be forged in the heat of Eldorado Canyon, was Tevis’ real reward.

And now, we had new information! Data on which to base future decisions, like electrolyting more and earlier, so we can do better next time.

Meanwhile, Atlas was back to his perky self as we loaded him up for a few hours’ trek to the fairgrounds in Winnemucca.

Along the way, I assessed my various battle scars: a stellar bruise on my right bicep (still visible as I write this story, over two months later!), another on my right quad, a scabby dent in my right knee, and bruising almost all the way around my right foot from its wresting match with my stirrup during our fall in Granite Chief.

The thing that hurt most, though, was good old fashioned DOMS. This was by far the worse case of delayed onset muscle soreness I’d ever experienced! While Atlas trotted around his pen and rolled blissfully in the Winnemucca sand, I could barely ease myself in and out of the trailer.

And that, my friends, inspired me to do a deep dive on the science behind DOMS – most particularly, how it can be minimized and treated. I’ve found some surprisingly helpful answers, and I’m working on a mini-course to share what I’ve learned.

The (free) DOMS mini-course will be ready in December. Be sure you’re signed up for my newsletter to get a heads up when I release it!

I had been following you during the ride (being a long-time blog reader) and knew you didn’t get the completion, but I knew nothing about the Choke! I’ve never witnessed a choke before, it sounds scary

Did you ever find out anything about the river? Did everyone experience the same high water? Your tale has this before you noticed a gait issue, any chance the high river had something to do with hind end?

Crazy, right? But we learned that choke is actually not uncommon among endurance horses, due to the dehydration factor. One vet compared it to eating Triscuits with a dry throat. Somebody said there were actually 2 other chokes at Tevis that day!

I wondered the same thing about the river and his hindquarters! I didn’t feel anything before that, and it started shortly after, so it’s entirely possible that some weird motion or slip was a factor. I’m pretty darn sure we were at the right place in the river. Some other riders came through behind us in the same spot and commented on the depth as well.

Love this! Thank you again for doing such a great job with him. I can’t WAIT until next year!!

Thank YOU so much for the opportunity! Best ride ever!!

Oh. I ugly cried reading this. Congratulations on riding the whole trail and taking amazing care of Atlas. I’m so sorry about the end. Your writing is beautiful. This part in particular gave me chills:

“The world seemed somehow bigger now, more hollow and lonesome and mysterious. We’d come so far, seen so much. Yet it still felt like a kind of beginning, this solitary trot into the night.”

DOM!!! I always love hearing from you. And, thank you SO much. 🙂 🙂

Oh, somehow I missed when you posted your full story! As always, you have such a way with words, and I could so easily visualize parts of the trail along the way. It was wonderful to finally be able to meet in person, the only bummer is not enough time to have extended socializing! I’m sad for you and Atlas to have not gotten that completion, but you handle it with the kind of grace that is humbling and inspiring…may we all have that same level of sportsmanship and horsemanship when it comes to the ups and downs of the endurance trail. Hope that our paths will cross at a ride again!

OMG, it was SO COOL to meet you in person at last! Any chance you’ll be there in 2025??

I will be there! Crewing, as usual….but I’ll be there! Are you going to give it another go?!?

Yay! Yes, assuming all goes well, Atlas and I are going to try again. 🙂

That’s awesome! I’ll plan on seeing you there again!

Sweet!!!